Social belonging, compassion, and kindness: Key ingredients for fostering resilience, recovery, and growth from the COVID-19 pandemic

George M. Slavich a , Lydia G. Roosb and Jamil Zakic a Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; b Health Psychology PhD Program, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC, USA; c Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

ABSTRACT Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to increases in anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, burnout, grief, and suicide, particularly for healthcare workers and vulnerable individuals. In some places, due to low vaccination rates and new variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerging, psychosocial strategies for remaining resilient during an ongoing multi-faceted stressor are still needed. Elsewhere, thanks to successful vaccination campaigns, some countries have begun reopening but questions remain regarding how to best recover, adjust, and grow following the collective stress and loss caused by the pandemic.

Method: Here, we briefly describe three evidence-based strategies that can help foster individual and collective recovery, growth, and resilience: cultivating social belonging, practicing compassion, and engaging in kindness.

Results: Social belonging involves a sense of interpersonal connectedness. Practicing compassion involves perceiving suffering as part of a larger shared human experience and directing kindness toward it. Finally, engaging in kindness involves prosocial acts toward others.

Conclusions: Together, these strategies can promote social connectedness and help reduce anxiety, stress, and depression, which may help psychologists, policymakers, and the global community remain resilience in places where cases are still high while promoting adjustment and growth in communities that are now recovering and looking to the future.

As Dedoncker et al. (2021), Zaki (2021), and others have suggested, a transition ( to a new normal) also provides a unique opportunity to grow by:

“identifying new techniques for bolstering resilience

and reconsidering what life should look like

in order to achieve a more healthy, sustainable, equitable, and enjoyable future.”

To help accomplish these goals, we briefly describe three key evidence-based strategies that psychologists, policymakers, and individuals can use to promote psychosocial resilience during the pandemic, as well as recovery, adjustment to a new normal, and growth after the pandemic subsides. These strategies involve cultivating social belonging, practicing compassion, and engaging in kindness (Figure 1).

REFERENCES: SOCIAL SAFETY AND PROTECTION

Akhtar S, Barlow J. 2018. Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 19:107–22

Allen KA, Vella-Brodrick D, Waters L. 2016. Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 33:97–121

Borman GD, Rozek CS, Pyne J, Hanselman P. 2019. Reappraising academic and social adversity improves middle school students’ academic achievement, behavior, and well-being. PNAS 116:16286–91

Clark DA, Beck AT. 1999. Scientific Foundations of Cognitive Theory of Depression. New York: Wiley

Creswell JD, Pacilio LE, Lindsay EK, Brown KW. 2014. Brief mindfulness meditation training alters psychological and neuroendocrine responses to social evaluative stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 44:1–12

Crum AJ, Akinola M, Martin A, Fath S. 2017. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 30:379–95

DeWall CN, MacDonald G, Webster GD, Masten CL, Baumeister RF, et al. 2010. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol. Sci. 21:931–37

Eberhardt JL. 2019. Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do. New York: Viking

Goyer JP, Cohen GL, Cook JE, Master A, Apfel N, et al. 2019. Targeted identity safety interventions cause lasting reductions in discipline citations among ethnic-minority boys. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 117:229–59

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. 2009. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc.

Hofmann SG, Grossman P, Hinton DE. 2011. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31:1126–32

Hofmann SG, Otto MW. 2017. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: Evidence-Based and Disorder-Specific Treatment Techniques. New York: Routledge. 2nd ed.

Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. 2017. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am. Psychol. 72:517–30

King CA, Arango A, Kramer A, Busby D, Czyz E, et al. 2019. Association of the youth-nominated support team intervention for suicidal adolescents with 11- to 14-year mortality outcomes: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 76:492–98

Kross E, Ayduk O. 2017. Self-distancing: theory, research, and current directions. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 55:81–136

Meyer HC, Odriozola P, Cohodes EM, Mandell JD, Li A, et al. 2019. Ventral hippocampus interacts with prelimbic cortex during inhibition of threat response via learned safety in both mice and humans. PNAS 116:26970–79

Miller GE, Brody GH, Yu T, Chen E. 2014. A family-oriented psychosocial intervention reduces inflammation in low-SES African American youth. PNAS 111:11287–92

Patton GC, Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Butler H, et al. 2006. Promoting social inclusion in schools: a group-randomized trial of effects on student health risk behavior and well-being. Am. J. Public Health 96:1582–87

Shields GS, Spahr CM, Slavich GM. 2020. Psychosocial interventions and immune system function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA Psychiatry. In press.

Slavich GM, Shields GS, Deal BD, Gregory A, Toussaint LL. 2019. Alleviating social pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of forgiveness and acetaminophen. Ann. Behav. Med. 53:1045–54

Walton GM, Cohen GL. 2011. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science 331:1447–51

Williams KD, Nida SA. 2014. Ostracism and public policy. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 1:38–45

Worthington EL Jr. 2013. Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Theory and Application. New York: Routledge

Strategies for promoting Social Safety and Reducing Social Threat

Social Safety Theory

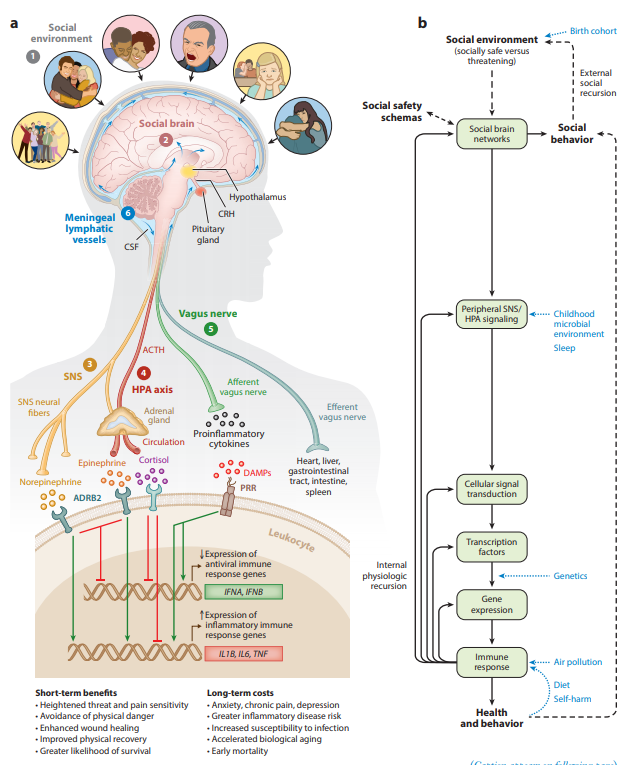

Social Safety Theory is grounded in the understanding that the primary purpose of the human brain and immune system is to keep the body biologically and physically safe. To accomplish this challenging task, humans developed a fundamental drive to create and maintain friendly social bonds and to mount anticipatory biobehavioral responses to social, physical, and microbial threats that increased risk for physical injury and infection over the course of evolution. (a) Accordingly, the brain continually monitors the

(●1 ) social environment, interprets social signals and behaviors, and judges the extent to which its surroundings are socially safe versus threatening. These appraisals are subserved by the

(●2 ) amygdala network, mentalizing network, empathy network, and mirror neuron system (i.e., the social brain). When a potential social threat is perceived, the brain activates a multilevel response that is mediated by several social signal transduction pathways—namely, the

(●3 ) SNS, (●4 ) HPA axis, (●5 ) vagus nerve, and

(●6 ) meningeal lymphatic vessels. These pathways enable the brain to communicate with the peripheral immune system and vice versa. Whereas the main end products of the SNS (i.e., epinephrine and norepinephrine) suppress transcription of antiviral type I interferon genes (e.g., IFNA, IFNB) and upregulate transcription of proinflammatory immune response genes (e.g., IL1B, IL6, TNF), the main end product of the HPA axis (i.e., cortisol) generally reduces both antiviral and inflammatory gene expression but also can lead to increased inflammatory gene expression under certain physiologic circumstances (e.g., glucocorticoid insensitivity/resistance).

The vagus nerve in turn plays a putative role in suppressing inflammatory activity, whereas meningeal lymphatic vessels enable immune mediators originating in the CNS to traffic to the periphery, where they can exert systemic effects. (b) This multilevel “Biobehavioral Response to Social Threat” is critical for promoting well-being and survival.

However, it can also increase risk for negative health and behavioral outcomes when it is sustained by internal physiologic or external social recursion.

Several factors can also moderate these effects, including birth cohort, childhood microbial environment, sleep, genetics, air pollution, diet, and self-harm behavior.

A person’s developmentally derived social safety schemas play a particularly important role in this multilevel process as they shape how social-environmental circumstances are appraised. Social safety schemas thus influence neurocognitive dynamics that initiate the full range of downstream biological interactions that ultimately structure disease risk and human behavior.

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropin hormone; ADRB2, β2-adrenergic receptor; CNS, central nervous system; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; HPA, hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

Adapted with permission from Slavich & Cole (2013), SAGE Publishing; Slavich & Irwin (2014), American Psychological Association; and Slavich & Sacher (2019), Springer Nature.

The Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (LEDS; Brown and Harris, 1978) remains the gold standard in stress assessment, regardless of the changing global conditions in the last 4 decades.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5066570/pdf/nihms811282.pdf

Life Stress and Health: A Review of Conceptual Issues and Recent Findings

George M. Slavich1 1Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Abstract:

Life stress is a central construct in many models of human health and disease. The present article reviews research on stress and health, with a focus on (a) how life stress has been conceptualized and measured over time, (b) recent evidence linking stress and disease, and (c) mechanisms that might underlie these effects. Emerging from this body of work is evidence that stress is involved in the development, maintenance, or exacerbation of several mental and physical health conditions, including asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, anxiety disorders, depression, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, stroke, and certain types of cancer. Stress has also been implicated in accelerated biological aging and premature mortality. These effects have been studied most commonly using self-report checklist measures of life stress exposure, although interview-based approaches provide a more comprehensive assessment of individuals’ exposure to stress. Most recently, online systems like the Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN) have been developed for assessing lifetime stress exposure, and such systems may provide important new information to help advance our understanding of how stressors occurring over the life course get embedded in the brain and body to affect lifespan health. Keywords stress; measurement; mechanisms; cytokines; inflammation; interventions; STRAIN; health; disease; risk; transformational teaching; classroom instruction

This tremendous interest in stress makes sense given the fundamental drive that humans have to better understand life’s circumstances and factors that ultimately impact survival. At the same time, viewing stress as an obvious trigger of disease—or as a construct that has a face-valid, commonly agreed upon definition—has led to substantial complication and confusion. Even in the scientific literature on stress and health, the construct of “stress” is frequently described in different ways and often with little detail or specificity. Likewise, although it has long been assumed that stress affects health, exactly how stress gets “under the skin” to promote disease has remained largely unknown. This has occurred in part because scientists have only recently developed the tools that are necessary to assess biological processes that link experiences of stress with disease pathogenesis. The purpose of this article is to briefly review contemporary ideas and research on stress and health. First, I examine some ways in which stress has been conceptualized and defined over the years. Second, I describe self-report and interview-based instruments that have been developed to assess life stress exposure. Third, I summarize recent findings linking stress and health and mechanisms that might underlie these effects. Fourth, I highlight the emerging focus on examining associations between lifetime stress exposure and health. Finally, I introduce some techniques that instructors can use to teach students about stress and healt

…

Stress and Health These developments in the conceptualization and measurement of life stress have helped greatly advance the science of stress and health. Indeed, nowadays, there is little debate about whether life stress plays a role in affecting health. As summarized in Figure 1, extensive research has examined these effects, and the take-home message from this literature is that stress exposure increases risk for poor clinical outcomes across a variety of major health conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis (Cutolo & Straub, 2006), depression (Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999; Monroe, Slavich, Torres, & Gotlib, 2007), cardiovascular disease (Kivimäki et al., 2006), chronic pain (Loeser & Melzack, 1999), human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS (Leserman, 2008), ovarian cancer (Lutgendorf et al., 2013), and breast cancer (Bower, Crosswell, & Slavich, 2014; Lamkin & Slavich, 2016). Stress has also been implicated in accelerated biological aging and premature mortality (Epel et al., 2004; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; for a review, see Cohen, JanickiDeverts, & Miller, 2007). Mechanisms Linking Stress and Health Given that life stress is associated with so many different health outcomes, researchers have recently attempted to identify whether stress increases risk for different disorders through a common biological pathway. One of the most recent and potentially important findings in this context involves the discovery that stress can upregulate components of the immune

system involved in inflammation (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004; Slavich & Irwin, 2014). Moreover, consistent with the stress–health links described above, there is emerging evidence showing that stressors involving interpersonal loss and social rejection are among the strongest psychosocial activators of molecular processes that underlie inflammation (Murphy, Slavich, Chen, & Miller, 2015; Murphy, Slavich, Rohleder, & Miller, 2013; for a review, see Slavich, O’Donovan, Epel, & Kemeny, 2010). Although inflammation is typically thought of as the body’s primary response to physical injury and infection, researchers have recently identified that inflammation plays a role in several of the most burdensome and deadly diseases (Couzin-Frankel, 2010; Slavich, 2015), thereby making inflammation a potential common pathway linking stress with several disease states.

Kagan, J., 2016. An overly permissive extension. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11, 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635593.

Abstract

In this article, I describe how the current practice of classifying as a stressor any event that is accompanied by a change in any of a number of biological or behavioral measures—even when it is not accompanied by a long-term compromise in an organism’s health or capacity to cope with daily challenges—has limited the utility of this concept. This permissive posture, which began with Selye’s writings more than 65 years ago, is sustained by the public’s desire for a simple term that might explain the tension generated by the threat of terrorists, growing economic inequality, increased competiveness in the workplace or for admission to the best universities, rogue nuclear bombs, and media reports of threats to health in food and water. I believe that the concept stress should be limited to select events that pose a serious threat to an organism’s well-being or discarded as too ambiguous to be theoretically useful.

Life Stress and Health: A Review of Conceptual Issues and Recent Findings

George M. Slavich, 1 1Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Abstract:

Life stress is a central construct in many models of human health and disease. The present article reviews research on stress and health, with a focus on

(a) how life stress has been conceptualized and measured over time,

(b) recent evidence linking stress and disease, and

(c) mechanisms that might underlie these effects.

Emerging from this body of work is evidence that stress is involved in the development, maintenance, or exacerbation of several mental and physical health conditions, including asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, anxiety disorders, depression, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, stroke, and certain types of cancer. Stress has also been implicated in accelerated biological aging and premature mortality. These effects have been studied most commonly using self-report checklist measures of life stress exposure, although interview-based approaches provide a more comprehensive assessment of individuals’ exposure to stress. Most recently, online systems like the Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN) have been developed for assessing lifetime stress exposure, and such systems may provide important new information to help advance our understanding of how stressors occurring over the life course get embedded in the brain and body to affect lifespan health.

Keywords stress; stress; measurement; mechanisms; cytokines; inflammation; interventions; STRAIN; health; disease; risk; transformational teaching; classroom instruction

Given the complexity of the psychosocial determinants underlying depression and anxiety, it is challenging to identify Asian Americans at high risk of developing these psychiatric disorders, particularly given that they are more reluctant to disclose their mental health status to others.3 17 Thus far, a few biomarkers have been used to predict depression, including cytokines and inflammatory markers, oxidative stress markers, endocrine markers, energy balance hormones, genetic/epigenetic factors and structural and functional brain imaging.

18 Emerging evidence suggests that the gut microbiome also plays an important role in human mental health via the microbiome–gut–brain axis, a bidirectional network that enables the gut microbiome to affect the brain and mental health through immune, neural and hormonal pathways.19 The gut microbiome is the collection of all genomes of the microbes in the human gastrointestinal tract.20 The human gut hosts tens of trillions of microbes, representing 500 species on average.21 22 Notably, it is heavily influenced by an individual’s sociodemographic characteristics, changes in diet, lifestyle, stress and geographic environment, all of which represent significant risk factors for depression and anxiety among Asian immigrants.23 24

More specifically, migration from non Western nations to the USA is associated with a loss in the gut microbial diversity and function in a manner that may predispose Asian immigrants to high risk of metabolic diseases and mental disorders.23 Therefore, subsequent changes in both the diversity and function of the gut microbiome after migration provide a unique opportunity to study how living environment in the USA represents an external stimulus that affects immigrants’ mental health in the context of stress, discrimination and acculturation.23 25 26 Finally, when exploring the impact of psychosocial determinants and the gut microbiome on mental health, it is important to address sleep quality.27 Asian Americans are more likely to report short sleep duration than their white peers (33% vs 28%).28 Sleep disturbance is one of the most prominent symptoms experienced by those with depression and anxiety disorder and is incorporated into the diagnostic criteria and definitions of these disorders.29–31 Moreover, chronic stress frequently manifests as increases in sleep disturbance and/or changes in sleep patterns.32 Daily racial microaggressions have been associated with poorer sleep quality and shorter sleep duration the following day among Asian Americans.33 Additionally, the gut microbiome has been associated with sleep disturbance and metabolic disorders.34 35 Considered together, therefore, it is critical to examine psychosocial and biological pathways that might underlie depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance in Asian Americans in the context of migration and acculturation among Asian immigrants in the USA.

Human diseases are extremely complex. To address scientific and healthcare challenges in this context, we leverage the power of cutting-edge tools from several disciplines, including psychology, neuroscience, immunology, molecular biology, genetics, and genomics. We accomplish by this employing a team science approach to the work we do. We have in-house expertise in several areas, but we also proudly partner with investigators and organizations from across UCLA and around the world to help solve our most important and pressing problems in healthcare and the health sciences. In short, we believe we can accomplish much more by working together than by working alone.

Our current scientific portfolio includes 175+ research projects spanning 95 institutions and 22 countries. Their common unifying feature is a primary focus on scientific innovation, collaboration, and impact. We only pursue projects that have the ability to greatly improve human health, healthcare, or both.

Central to these projects is the idea that stress doesn’t just increase risk for a few select disorders, but rather is a common risk factor for a wide variety of serious mental and physical health problems that dominate present-day morbidity and mortality. Stress can manifest itself on an individual level (e.g., “psychological stress”) but also on a collective level — for example, in work, healthcare, and school environments. Our hope is that by better understanding these links, we can help to reduce stress and enhance human health and well-being.

We are always looking to partner with highly inspired, like-minded people and organizations at UCLA and beyond. If you are passionate about advancing the health sciences and/or improving healthcare, we look forward to hearing from you on our Contact page.

Social belonging and health

Translational psychoneuroimmunology

Human pluripotent stem cells and psychiatry

mHealth tools for identifying toxic stress in primary care

Modifiable cognitive and psychosocial resilience factors for reducing stress reactivity and improving human health

Social and biological risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behavior

Social and biological determinants of health disparities

Factors influencing clinical outcomes in ovarian, breast, lung, and prostate cancer

Social, behavioral, and biological factors influencing biological aging

Organizational strategies for reducing stress and enhancing collective well-being

Belonging: Review conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and future research

Kelly-Ann Allen, Margaret L. Kern,Christopher S. Rozek,Dennis M. McInerney &George M. Slavich

Pages 87-102 | Received 21 Sep 2020, Accepted 18 Jan 2021, Published online: 10 Mar 2021

ABSTRACT

Objective: A sense of belonging – the subjective feeling of deep connection with social groups, physical places, and individual and collective experiences – is a fundamental human need that predicts numerous mental, physical, social, economic, and behavioural outcomes. However, varying perspectives on how belonging should be conceptualised, assessed, and cultivated has hampered much-needed progress on this timely and important topic. To address these critical issues, we conducted a narrative review that summarizes existing perspectives on belonging, describes a new integrative framework for understanding and studying belonging, and identifies several key avenues for future research and practice.

Method: We searched relevant databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and ClinicalTrials.gov, for articles describing belonging, instruments for assessing belonging, and interventions for increasing belonging.

Results: By identifying the core components of belonging, we introduce a new integrative framework for understanding, assessing, and cultivating belonging that focuses on four interrelated components: competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions.

Conclusion: This integrative framework enhances our understanding of the basic nature and features of belonging, provides a foundation for future interdisciplinary research on belonging and belongingness, and highlights how a robust sense of belonging may be cultivated to improve human health and resilience for individuals and communities worldwide.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Belonging is a fundamental human need that all people are driven to satisfy.

However, there is disagreement in the literature regarding how a person should go about increasing their sense of belonging.

There is also little consensus regarding how belonging should be conceptualized and measured.

What this topic adds:

The review article draws together disparate perspectives on belonging and harnesses the strengths of this multitude of perspectives to help advance the field.

The paper provides a framework that can help inform researchers, practitioners, and individuals seeking to increase a sense of belonging in themselves and in the organizations and groups in which they work and live.

We posit that competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions are central elements in strategies that can be used to increase our individual and collective sense of belonging for the betterment of society.